Like the Commonwealth Act of 1934 or Philippine Independence Act of 1934, the Filipino people were never asked if we wanted to secede from the U.S. in 1946. And yet in the Pledge of Allegiance, Americans swear:

” . . . one nation under God, indivisible with liberty and justice for all.”

On Nov. 6, 2012, a referendum was held in Puerto Rico, and only a tiny 5.6 percent of Puerto Ricans voted for independence.

On Sept. 18, 2014 a referendum was held in Scotland to determine if Scotland should be independent. The Scottish people voted no to independence

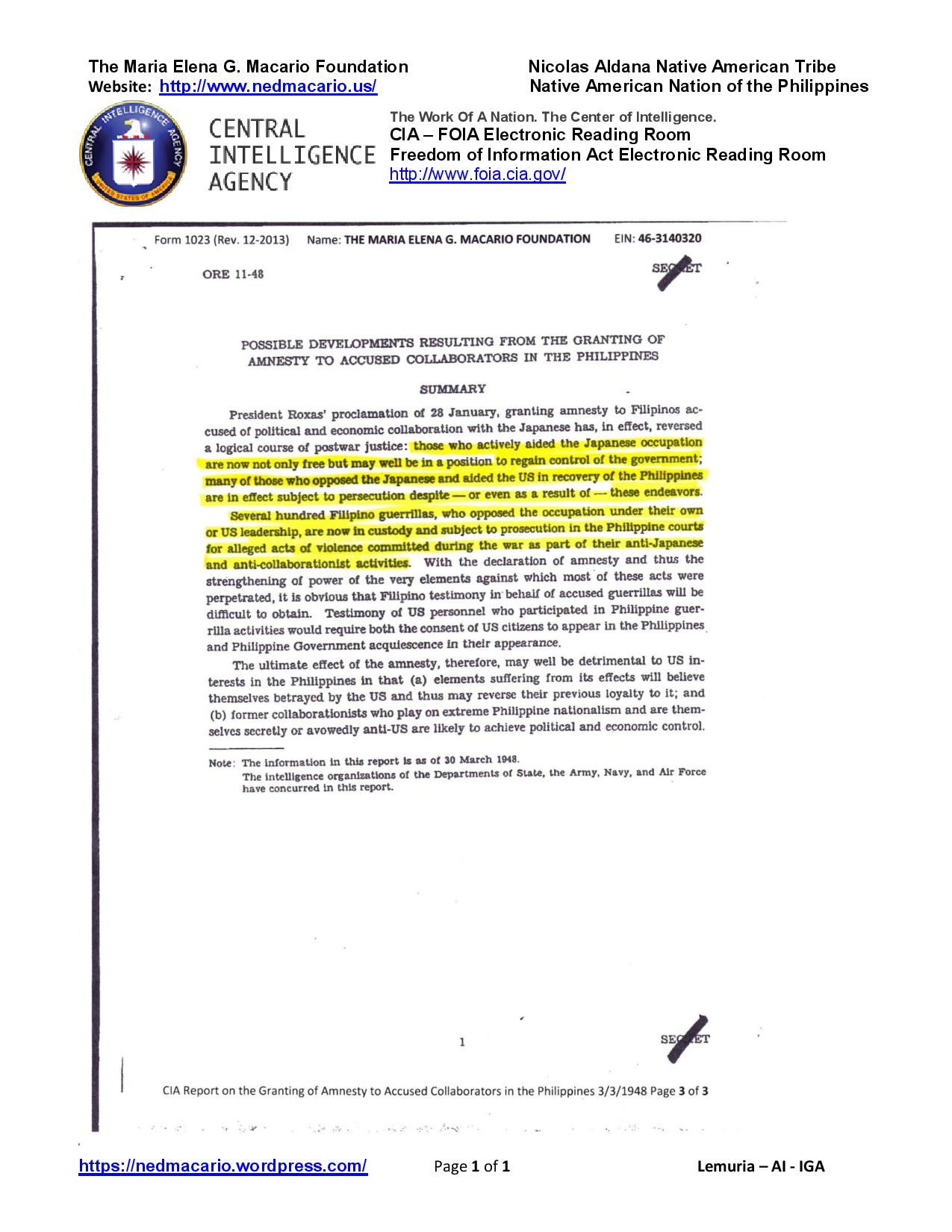

All these referenda should remind Americans and Filipinos that there was no referendum held when known Japanese collaborator Manuel A. Roxas sought independence for the oil, gas and mineral rich, Philippines, then a U.S. Territory. The US Senate prematurely, irresponsibly and unconstitutionally granted the Philippines dependent-independence when the Treaty of Manila was ratified of Manila on 22 October 1946.

The Volstead Act was repealed. The Takata air bags were recalled but the 1946 Treaty of Manila has not been rescinded.

On Dec. 21, 2015 when Steve Harvey realized his mistake in announcing Miss Colombia as the winner instead of Miss Philippines, he immediately corrected his mistake. Comedians are better than American politicians.

The U.S. Senate to this day continues to fund, aid and abet oppression, treason and corruption in the former U.S. territory using American taxpayers’ money through the World Bank.

Anyone on this planet who still believes countries like the former U.S. territory, the Philippines, is ready for independence and self-rule:

a.) Should have his or her head examined, starting with the U.S. Senate.

b.) Should live in the Philippines and experience first-hand the hell on earth.

c.) Must have ulterior motives.

Here is the Treaty of Manila that granted dependent-independence to the Philippines, a U.S. territory and created the hell on earth. We were handed over to oligarch-traitors who wanted to escape justice for collaborating with the Japanese during WWII.

“The Treaty of Manila of 1946 (61 Stat. 1174, TIAS 1568, 7 UNTS 3), formally the Treaty of general relations and Protocol,[1] is a treaty of general relations signed on 4 July 1946 in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines.

The United States GRANTED the PHILIPPINES INDEPENDENCE, and the treaty provided for the recognition of that independence. The treaty was signed by Ambassador Paul V. McNutt as a representative of the United States and President Manuel Roxas representing the Philippines.

The treaty became effective in the United States on 22 October 1946, when it was ratified by the Senate (79th Congress).”

The 1946 Treaty of Manila

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Manila_(1946)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UX660r0CNE